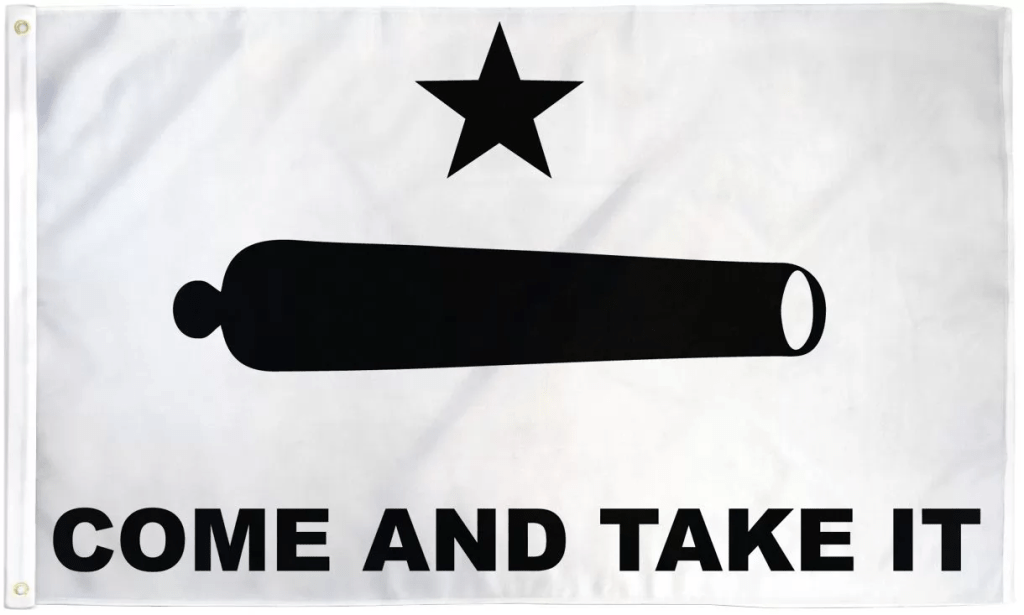

Last Friday, we posted commentary about the news that last week, the Texas National Guard began flying the Gonzales Flag (under the Stars and Stripes) in front of their headquarters in Austin, long capital of the Lone Star Republic and now the Lone Star State.

It’s a slogan of defiance against government tyranny. It has roots in antiquity that continues to inspire freedom-loving and liberty-loving people today. This English updating of the Greek (Spartan) molṑn labé (meaning “come and take them”) triggers strong emotions. It is a powerful challenge to would-be gun grabbers – tyrants however they came to office. Seeking to steal arms from people must not ever come without a dear cost. For the Texian rebels in the embattled town of Gonzales, these words were not mere tough talk. They were words the Texians were willing to die for. Not because their little cannon was any great shakes, but for the principle behind it.

TPOL summarizes what Ammo.com writes about its history:

The story begins in 1831. Texians (an old name for the people of Texas, Anglo, Hispanic, AmerInd, German, French, etc.) in Gonzales, then a part of Mexico, requested a cannon from their feds to defend themselves from Comanche raids. The cannon itself was of little military use. It probably served more as a visual deterrent to the hostiles than a military one.

Curiously, Gonzales was one of the communities preferring Mexican rule to independence, even after relations between Mexico’s fedgov and the Texians began to sour. Indeed, the town declared its allegiance to Santa Anna’s government. But on September 10, 1835, a Mexican soldier beat up a Gonzales Texian, sparking widespread outrage. So the federal government decided to retrieve the cannon before it was turned on their own troops. Oh, my, does that sound familiar? It went over very, very well. Colonel Domingo de Ugartechea sent out Corporal Casimiro De León and five soldiers of the Second Flying Company of San Carlos de Parras.

Emboldened by other Mexican states (not just Texas) in open revolt, the Texians refused to return the weapon. De León and his men were made hostage: placed under arrest. [Hint! Hint!] It really wasn’t about the cannon: Texians were worried that the FedGov planned to use recent unrest as an excuse to disband local militias, which the Texians considered absolutely essential for freedom and safety.

So they buried the cannon in George W. Davis’s peach orchard, and do other things to delay the arrival of 100 Federale dragoons. By the time they arrived, there was a Texian force 140 strong. On October 1, 1835, these men voted and decided that if the fedgov wanted the cannon back, they were going to have to fight for it. This was the last spark that ignited the wildfire of the Texas Revolution.

The Gonzales Flag is a simple design but a stark gauntlet thrown at Mexican federal power. It was nothing more than a star, the cannon in question, and the old Spartan slogan updated for modern times: “Come and Take It.” On October 2, when Lieutenant Castañeda requested return of the cannon under the terms of the original agreement, the Texians simply pointed to the weapon sitting 200 yards behind them: “There it is. Come and take it.” Once fighting started between the settlers and the federales, Texians commissioned a flag from local ladies to fly over the cannon. “Come and Take It” was both a cry of freedom and a taunt to tyrants. And still is.

Texians didn’t wait for an attack, but rather went on an offensive of their own, using the cannon. They had nothing in the way of cannonballs. Instead, scrap metal was used as ammo fired at the oncoming Mexican forces. James C. Neill, a War of 1812 veteran, commanded Texas’ first artillery regiment. The local Methodist minister gave the assault his blessing, invoking the Spirit of 1776. The Texians also swore loyalty to another constitution – the Mexican one of 1824, which Santa Anna had repudiated in favor of greater centralized control. The commanding officer of federal forces, ironically, was in ideological solidarity with the settlers, but his first duty was as a soldier.

When all was said and done, this minor battle, lasting only a few hours, forced the retreat of Mexican forces. Two Mexican soldiers died. The only Texian casualty was a man thrown from his horse who suffered a bloody nose. The Battle of Gonzales represented a final and definitive break between Texian settlers and the Mexican government. There would be no going back to business as usual. Word of the battle quickly spread to the States, where the event (initially known merely as “the fight at Williams’ place”) was lionized as “the Lexington of Texas.” Young men flocked to Texas to join the cause of freedom against military despotism.

Thousands of Texians did not back down from the increasingly bloody confrontation. By the end of 1835, all Mexican forces had been driven out of Texas. Santa Anna himself, failing to flee disguised as a woman, was held in chains by the Texians. He was forced to recognize their independence. A decade later, Texas joined the Union: a mistake in the opinion of many.

That the slogan of Spartan warriors would resonate with Texian forces thousands of years later, shows just how powerful an idea this is: Tyrants who wish to disarm a free people will get a fight. Government agencies and leaders that seize illegal, unconstitutional, and immoral power will face the consequences, on this earth or at Judgment Day.

The message to Uncle Joe and DC should be clear: back down or pay the price that Texan Guardsmen, Rangers, Public Safety, and ordinary citizens are prepared to pay. Secession? No, not necessarily and not a certainty by any means, despite that always being a strong contender. But certainly if the FedGov of Uncle Joe and the regressives do not start obeying the Constitution, they can expect serious consequences.